French Explorer Dumont d’Urville in New Zealand

Jules-Sebastian-Cesar Dumont d’Urville

The French explorer and captain Jules Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842) visited New Zealand on three separate occasions. In April 1824 for 2 weeks on the corvette (ship) Coquille as second in command to Louis-Isidore Duperrey; in January 1827 on the ship Astrolabe (Coquille renamed) and in 1840 on the Astrolabe along with a second, identical ship, the corvette Zélée and attempted, on two occasions, to reach the South Pole.

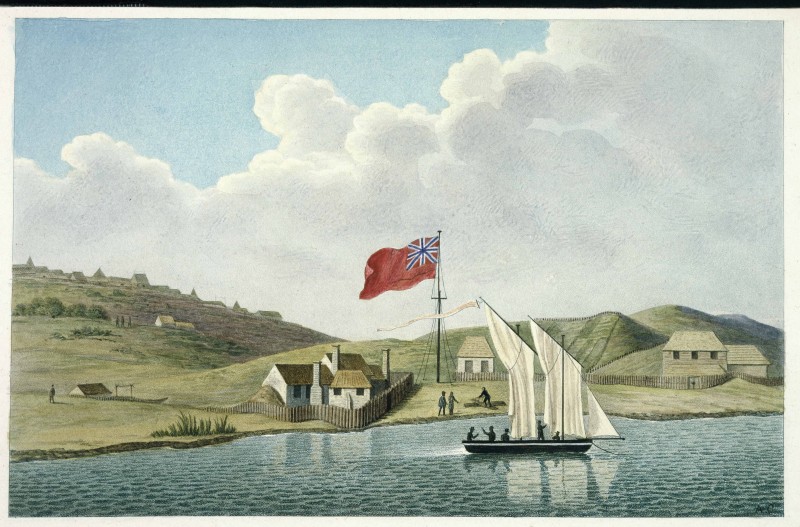

Keri Keri, Bay of Islands 1824 drawing by Jules Louis LeJeune, artist on the Coquille copied 1826 by Antoine Chazal. Ref: C082094. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Dumont d’Urville is not a well-known figure in New Zealand today. Sailors may recognise his name in Durville Island, located in the Marlborough Sounds, where they converge with Cook Strait. D’Urville also named the treacherous French Pass, which runs between Durville Island and the mainland, a very difficult channel that his ship sailed through. D’Urville also named nearby Croisilles Harbour (after his mother’s family). After his wife, he named Adele Island, now a celebrated stopover in Abel Tasman National Park, Pepin Island and the also Adélie penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) in Antarctica.

Durvillaea antarctica, the seaweed we know as bull kelp or rimurapa, found around the coasts of New Zealand and in Chile and Peru is also named after Dumont d'Urville.

Looking to French Pass with Durville Island in the distance. Used with permission, Shellie Evans, 2014 https://shorturl.at/ELLDK

Model of French naval warship, Corvette, similar to Astrolabe with approx 20 guns. On view National Marine Museum, Toulon Celia Hay (2024)

Like Captain James Cook (1728-1779), d'Urville’s three voyages of circumnavigation had both an exploratory and scientific purpose but also carried secret instructions to look for land suitable for colonisation. For France, recovering from years of revolution followed by the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, and his subsequent defeat in 1815, there was concern that Great Britain was becoming too successful as a global power with its expanding empire. France was being left behind.

Three voyages around the world

La corvette Coquille departed Toulon on 11 August, 1822 and returned to Marseilles 24 March 1825. La Coquille arrived Bay of Islands 3 April 1824 and departed after two weeks on 17 April 1824.

La corvette Astrolabe (Coquille renamed) departed Toulon 28 March 1826 on and returned 25 March 1829. Arrived Cape Farewell, Nelson on 1 January 1827 and departed from the Bay of Islands for 18 March 1827.

La corvette Astrolabe departed Toulon 7 September1837 and returned 6 November 1840. First Antarctica Voyage January – April 1840 departing from South America. Second Antactica Voyage departing and returning to Hobart during January 1840 but abandoned to preserve the health of his crew.

Edward Duyker, (2014), Dumont d’Urville, Explorer and Polymath[1], has written a comprehensive study of Dumont d’Urville's life using primary sources including d’Urville's reports, journals and letters. This provides a fascinating background to pre-Treaty Aotearoa New Zealand from a French perspective.

D'Urville the polymath

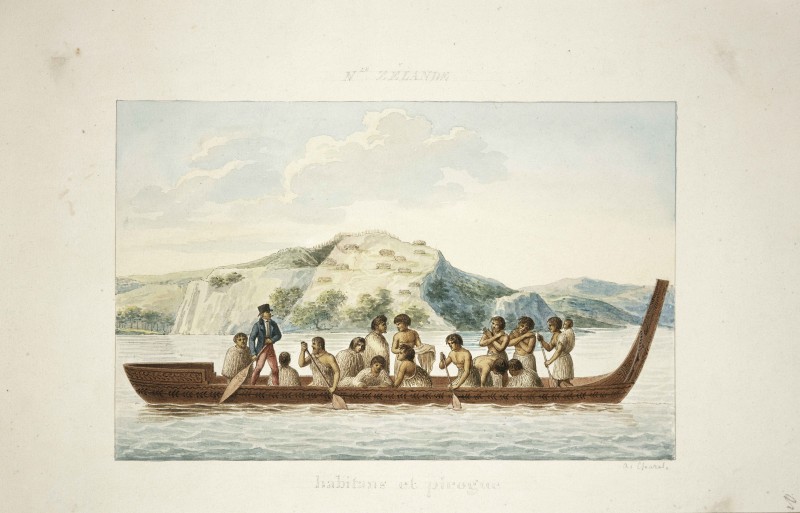

Jules LeJeune, artist on Coquille, under Duperrey and d'Urville during the 1824 visit to the Bay of Islands. The painting shows a waka greeting the French Corvette Coquille and lead by Rangatira Tuai who visited England in 1818/9.[2]

D’Urville was more than an explorer. Educated privately by his uncle, d’Urville learnt Latin, Greek, English, German, Italian, Russian, and later Chinese and Hebrew. His family survived the horrors of the French Revolution. As a linguist, during his voyages in the Pacific, d’Urville studied the local languages as tools to understand ethnography; the study of people, culture, customs.

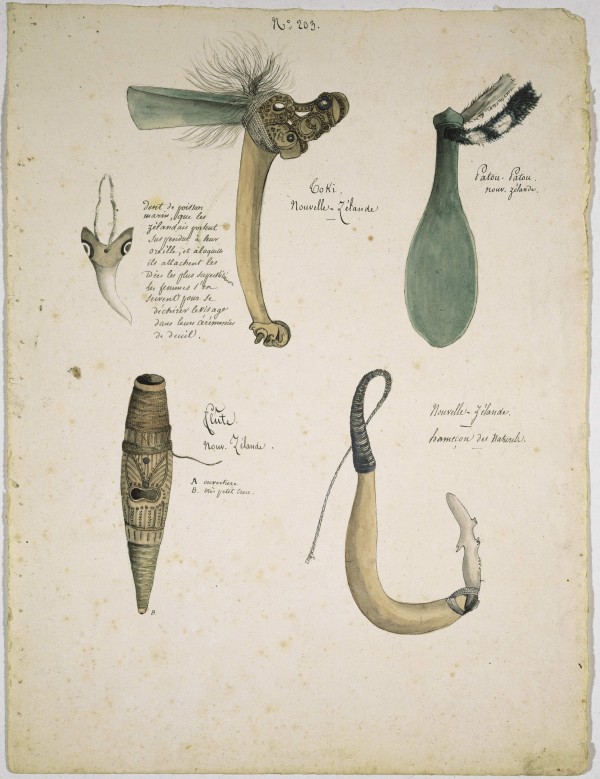

Chazal, Antoine, 1793-1854 :Nouvelle-Zelande. No 203. Toki. Patou-patou. Dent de poisson marin que les zelandais portent suspendue a leur oreille ... Flute. Hamecon des naturels. [1825 or 1826] Item link: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22770491

D’Urville, identified similarities in the islands of the Pacific based on their language, physical appearance and cultural practices. He believed that Polynesians has migrated from Asia into the Pacific and recognised 60 word common to both Polynesian and Malay which ‘attest to ancient communications'[3].

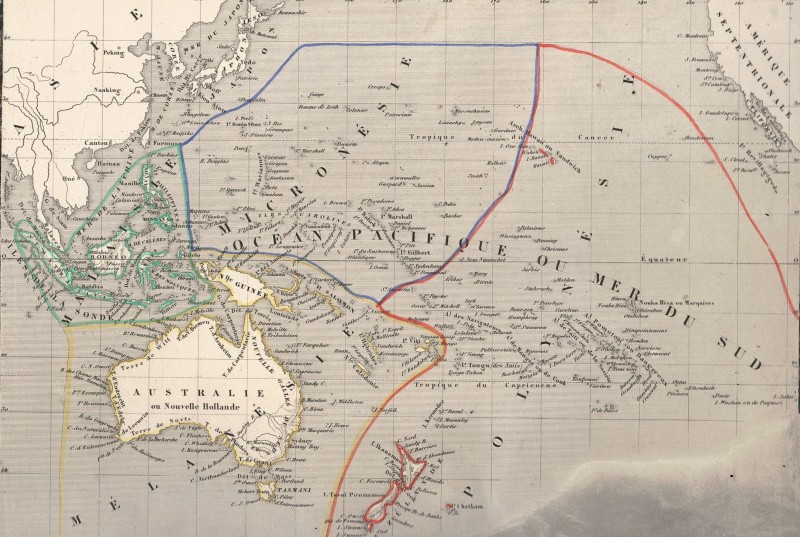

Map from Levasseur Atlas denotes Polynesia, Melanesia, Micronesia. Purchased by Celia Hay (Paris 2024)

He labelled the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago, Malaisie, made new definitions for the term ‘Polynésie and coined the terms Micronésia and Melanésia which we still use today.

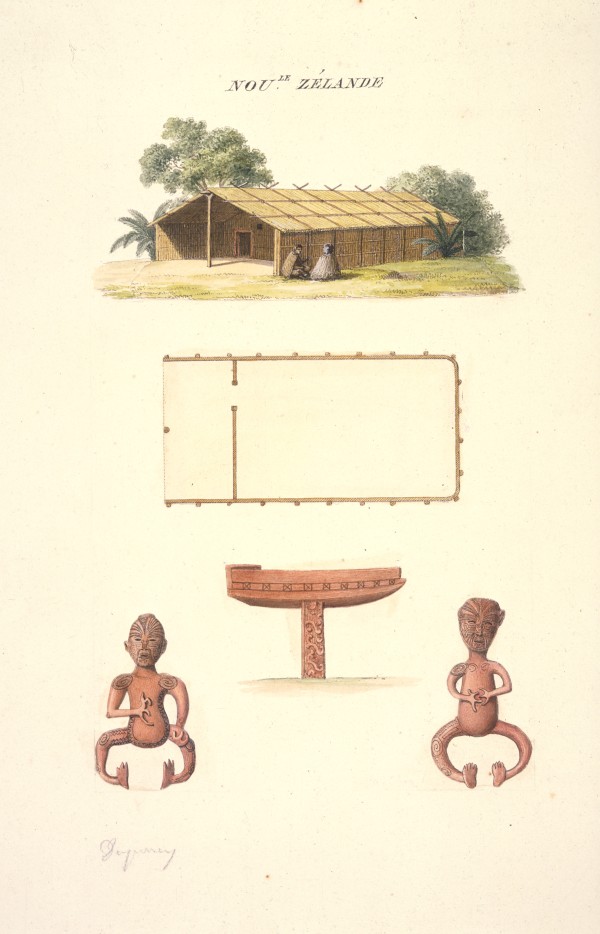

Chazal, Antoine 1793-1854 :Nou[vel]le-Zelande [1. Maison des naturels. 2. Plan de cette maison. 3. Tombeau. 4. Idoles]. Duperrey, no. 41. [Copied 1825 or 1826 from an original by Jules Lejeune done in 1824].

During the voyages, artists on board would sketch and paint images of places, people, plants, animals and artifacts. These were often completed or coloured by other artists, once the voyage had returned to France. Today, these images provide rare context to these journeys of so long ago.

Plants

With a fascination for the natural world, d’Urville actively went ashore to collect plant and insect specimens. Once back in France, after each voyage, d’Urville would work on preparing his journals for publication and specimens would be placed at the Museum d’histoire naturelle in Paris. The voyage of the Coquille resulted in nearly 3000 species of plants of which 400 were considered new and 1,200 specimens of insects including 300 previously unknown species.[4]

As a botanist d'Urville's has named after him, Hebe urvilleana and the buttercup Ranunculus urvilleanus and a species of grass tree Dracophyllum urvilleanum. There is also a genus of seaweeds Durvillaea, which includes the giant bull-kelp.

1837-1840 Voyage of Astrolabe and Zélée to the Southern Ocean

Food on Board

D’Urville departed Toulon on the Astrolabe for his 3rd circumnavigation, with a second ship, Zelée and with special instructions to sail to Antarctica and investigate if there existed opportunities for France. With limited ports to call into for food and water, d’Urville packed 14 months of supplies.[5]

Duyker writes:

Water on the vessels was stored in metal tanks of 900 and 1000 litres. We know that the Zélée was provisioned with 27,435 litres of wine, laid down in barrels of 250, 500 and 750 litres, intended to last 432 days; 1600 litres of brandy, intended to last 92 days; 590 kilograms of coffee, intended to last almost 14 months; 700 kilograms of sugar for 426 days; 74 kilograms of butter for 60 days; 3400 kilograms of salted lard for 230 alternate days; 550 kilograms of cheese to last 55 alternate days; 1395 kilograms of vegetables for 283 alternate days; over 4.5 tonnes of flour to last 92 days; and over 14 tonnes of sea biscuits (hard tack, pictured above) to last 288 days. Further more

- 642 kilos of tinned beef

- 400 kilos of sauerkraut

- 450 kilos of rice

Beef was preserved in 30-kilogram drums which involved injection of carbon dioxide. Three of the drums exploded during the voyage, rupturing their soldered seams. Although the beef looked fine, it smelt of putrefaction and, not surprisingly, was unpopular with the crew, who preferred salted beef.

To nourish the expected dysentery cases, the infirmary was supplied with a reserve of 100 kilograms of gelatine and 3700 kilograms of tinned meat and vegetables.

Each vessel had its own baker…400 litres of olive oil, to last 813 alternate days, and 50 kilograms of mustard…400 litres of vinegar. The latter was used as dressing for salad and for pickling, but it was also added to the drinking water (as was quick lime, presumably depending on the pH) to prevent putrefaction.

Similarly, 726 kilograms of salt was stowed on the Zélée for seasoning but also for preserving fresh supplies en route. Only modest quantities of salted beef (300 kilograms for 18 alternate days) and cod (80 kilograms for 8 alternate days) were loaded. They would soon have to replenished. Forty-one cubic metres of firewood, to last almost 11 months, were taken aboard.

Antarctic Adventure

The Astrolabe and the Zelee caught in Antarctic ice, watercolour by A. Mayer. (1838) State Library of New South Wales via Wikimedia Commons

During this voyage, d`Urville made two attempts explore Antarctica. In 1838, the ships sailed south from Tierra del Fuego however the two ships became trapped in pack ice which nearly proved disasterous. It took five days to cut through the ice along and a favourable wind, the ships were able to be freed and sailed north.

Not to be deterred, d`Urville embarked on a second attempt, sailing south from Hobart, Tasmania on 1 January 1840. Again sailing through icebergs "sheer walls of ice far higher than our masts; they overhung our ships." [6] By the 21 January, they had sighted land. This coast d'Urville named after his wife, Terre Adelie. The treacherous conditions made for a short stay and the ships had returned to Hobart by mid February.

French Settlement in Akaroa, 1840

D'Urville arrived in Akaroa via Otago and the Auckland Island in April 1840 and met a number of French whaling ships active off the southern coast of Banks Peninsula. Later, in August 1840, the French ship, Comte de Paris arrived with 63 emigrants to establish a colony, this was followed by the corvette, Aube commanded by Captain Lauvaud. Of the proposed colony, D'Urville wrote in his journal:

'Akaroa would be a very bad choice for a first settlement: it is not enough, in effect for a nascent colony to possess a vast and safe harbour, to shelter vessels, to have a chance of success; the colonists must be assured, not only of being able to live off the land, but also of producing food from the land which nurtures trade.

'A nascent colony must also establish easy communication with the interior of the country, in a manner which extends measurably as emigration bring new colonists. From all these perspectives, the port of Akaroa appeared to me disadvantageous to the foundation of a settlement; indeed, in my opinion, it would be a foolish enterprise to go and create, at the other extremity of the globe, French agricultural colonies in New Zealand opposite England’s Australian settlements, today undoubtedly successful….furthermore in time of war with England,, one would not think of defending such isolated possessions against British forces. [7]

A glass of New Zealand Wine

In April 1840, d'Urville returned to Kororāreka (Russell) in the Bay of Islands, for the third time. Te Tiriti of Waitangi had been signed on February 6 1840 ceding ownership of the land to Queen Victoria. D'Urville was uncertain how to respond to this news without instructions from France and knowing that French colonialists were about to establish a colony in Akaroa, on Banks Peninsula.

There was also rivalry between the Protestant British missionaries and the Roman Catholic priests headed by Bishop Pompallier. In his final days, d'Urville did visit the home of James Busby, recognised today as the Treaty House at Waitangi. Here he met with a Mr Flint, as Busby had returned to Sydney with his family to contest his land purchases. Mr Flint offered d'Urville a glass of Busby's wine.

From d'Urville's journal: [8]

While walking through Mr. Busby's property, I noticed a trellis, on which several vines of a large vine were twined. I asked Mr Flint if the vine had produced fruit in this climate, and... learned, with surprise, that people had already tried to make wine with grape products from New Zealand.

Arriving at his house, Mr. Flint offered me a glass of Port wine; I refused, but I accepted with pleasure to taste the product of the vineyard that I had just seen.

I was served a small, light white wine, full of fire, which I found had an excellent taste, and which I drank with pleasure. From this sample, I have no doubt that the cultivation of vines will expand greatly on the sandy hillsides of these islands, and soon, perhaps, the wine of New Zealand will be exported to the English possessions (colonies) in India.

Pictured above Korora-raka (Russell) c1831 painted by Barthélemy Lauvergne. Engraved by Sigismond Himely., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Tragic Death

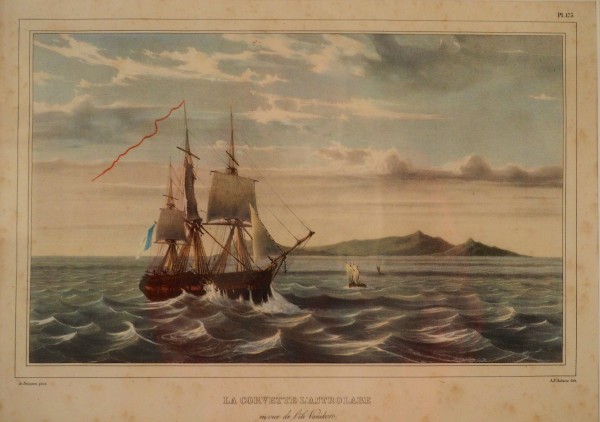

By Archives New Zealand La Corvette Astrolabe under the command of Captain d'Urville. Sainson, L. A. de, b. 1800 :L'Astrolabe dans la Passe des Francais. National Library of New Zealand.

D'Urville returned to Toulon in November 1840 to the profound relief of his wife Adelie and only surviving child, Jules. To complete d'Urville's reports of the voyage, they rented an apartment in Paris and Jules attended high school. Adelie and d'Urville were both plagued by medical issues.

On May 8 1842, the family boarded a train for Versailles to view the water fountains. On return to Paris, their train broke its axle and collapsed on the rails. A second train, crashed into it resulting in derailment. The coke from the fireboxes burst in flame and quickly ignited the wooden carriages which were locked shut. People could not escape. D'Urville, his wife Adelie and son, Jules perished in the inferno along with 200 other people. This was the worst train accident of the era and the tragedy rocked France.

Jules Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842) Explorer and Polymath

Celia Hay

February 2025

---

End Notes

[1] Edward Duyker, (2014), Dumont d’Urville, Explorer and Polymath, Otago University Press, New Zealand

[2] Chazal, Antoine, 1793-1854 :[Watercolours, proof engravings and aquatints by Antoine Chazal and others after drawings by Jules LeJeune and others for Duperrey's Voyage autour du monde ... Paris, 1822-1825]. Ref: C-082-089. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

[3] Ibid., p.306

[4] Ibid., p.163

[5] Ibid., pp.340 - 41

[6] P 436 ice

[7] Ibid., p.457 Akaroa

[8] The quotation has been translated from the history of the Voyage of Dumont d’Urville, Jacquinot Histoire du Voyage Vol IX. p194 In 1833, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/133647#page/201/mode/1up